Artificial Biotopes

Lehmbruck, Kolbe, Mies van der Rohe and Anne Duk Hee Jordan

11. June 2022 – 28. August 2022

The exhibition KÜNSTLICHE BIOTOPE (ARTIFICIAL BIOTOPES) at the Georg Kolbe Museum explores the enriching relationship between architecture, sculpture and nature. Presented in the large sculpture studio of the Georg Kolbe Museum, the works of three prominent figures of early 20th-century modernism are joined by ANNE DUK HEE JORDAN’s (b. 1978) living installation. In light of contemporary discourse, the exhibition takes the historical theme of man and nature to new dimensions. In her environments where organic materials meet motorized objects, the artist explores themes of transformation and transience. In the spirit of Donna Haraway’s “naturecultures,” Jordan imagines a world in which various agents beyond human beings interweave and react to each other. Here the organic and the artificially created exist symbiotically, blurring the boundaries between nature and culture.

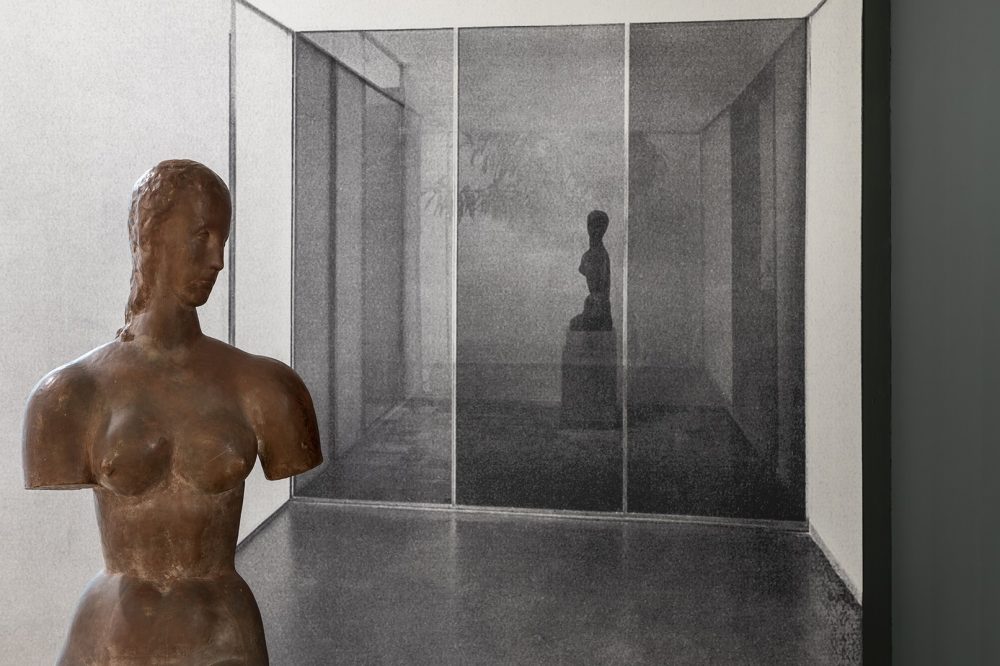

With their figurative sculptures, WILHELM LEHMBRUCK (1881–1919) and GEORG KOLBE (1877–1947) created an image of humanity that sought new forms for existential human questions. In the 1920s, LUDWIG MIES VAN DER ROHE (1886–1969) developed a radically modern architectural language, one that reached wide international appeal. His houses are functionally and aesthetically well-considered structures whose open floor plans combine the ideal of a permeable system with a vibrant material language. In his pivotal European work, Mies van der Rohe repeatedly integrated sculptures by Lehmbruck and Kolbe, creating artificial biotopes with plants, organic materials, water basins and reflections.

The New Organic Unity

In Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona Pavilion of 1928/29, Georg Kolbe’s sculpture “Der Morgen” adds a human scale to the austere cubic building. Concurrently, the human body in 1920s sculpture was conceived tectonically, composed of abstract geometric volumes. At the time, there was a fundamental attempt to create an interconnectedness, joining objective and functional architecture with autonomous sculpture. Mies van der Rohe was one of the few architects to consistently incorporate figurative sculpture into his architectural concepts. Like other modernist artists, he was inspired by a scientific, universal perspective of the world. New findings, especially from the field of life sciences, ushered in a view of reality as an organic whole. Forms and processes in nature were compared to aesthetic and mechanical aspects of technical devices and even to the structure of societies. In this regard, the figurative sculptures of Lehmbruck and Kolbe are placed not only as works of art in architecture but also as living bodies that are part of a superordinate system.

Nature as an Engine of Modern Architecture

The exhibition was developed in cooperation with the Kunstmuseen Krefeld in Haus Lange, which was designed by Mies van der Rohe in 1927. In the same year, Ernst Rentsch designed the residential and studio building that would later become the Georg Kolbe Museum. Kolbe knew the architects of modernism well, and his studio house in Berlin’s Westend reflects many elements of Neues Bauen (New Building), from which he created an ideal, individually-tailored space to live and work. The close link between nature and architecture can still be seen at the Georg Kolbe Museum today: A garden courtyard nestles between two austere buildings with large windows. Inside the brick walls, the sculptor and architect have preserved a piece of Berlin’s Grunewald, enclosing its tall, natural pines. The buildings with their subtle orientation to the garden, delicately linking indoor and outdoor spaces, reflect this connectedness.